OpenClaw and the Emergence of Personal AI Autonomy Infrastructure

Why OpenClaw matters less as a vulnerability story and more as a signal that personal autonomous agents have arrived.

OpenClaw (prev. MoltBot and Clawbot) has attracted a great deal of attention as a new kind of agentic risk, particularly after instances of exposed deployments surfaced through tools like Shodan. Much of the commentary has focused on visible vulnerabilities and the ease with which some instances were discovered online. While those concerns are valid, they risk obscuring what is actually important about OpenClaw.

At its core, OpenClaw is an open source agent designed to act as a personal assistant with the ability to connect to tools and applications. What differentiates it from a traditional assistant is autonomy. It can persist over time, reuse context, and take action without continuous human input. In that sense, OpenClaw is not an anomaly. It reflects a broader class of agentic systems that are becoming increasingly accessible to individuals as well as organisations.

As with most open source software, questions around security are expected. The same applies to agentic systems more broadly. Tool access, over-permissioning, and exposure through prompts, integrations, or network access are not unique to OpenClaw. Any agent that can interact with external systems carries these risks if it is deployed without care. Framing OpenClaw as exceptional in this regard misses the more general lesson that autonomy changes how failure and exposure emerge.

Autonomy is Moving Down the Stack

What makes OpenClaw genuinely interesting is not its implementation details or even its vulnerabilities. It is the change it represents in where autonomy is being placed and the ease of accessibility to that kind of advanced technological agency. Until recently, agentic systems largely lived inside enterprises, embedded in platforms, workflows, and centrally governed environments. OpenClaw highlights a different trajectory. Individuals are now standing up autonomous systems in their own environments, granting them real capabilities and long-lived access to personal tools and data.

Local-First Does Not Mean Low Risk

OpenClaw's local-first design is part of its appeal. A self-hosted agent feels private and contained, especially compared to a hosted service. That intuition is understandable, but it often creates false confidence.

Local deployment shifts responsibility rather than reducing risk. Authentication, network binding, credential storage, and update hygiene move from managed platforms to individuals. In practice, many users leave defaults in place, expose services unintentionally, or allow credentials to persist longer than intended. Risk accumulates quietly, without clear ownership or visibility.

This is not limited to home use. The same pattern appears in office environments, where locally run agents interact with internal tools, development systems, or shared resources. A single machine can become an unintentional bridge between systems that were never meant to connect.

Local-first agents can be powerful, but they still require governance. As autonomy becomes more distributed, security depends less on where an agent runs and more on whether its behaviour, permissions, and identity remain visible and controlled over time.Whilst in OpenClaw's case this is occurring in personal devices, this is also occurring through citizen development in businesses today. Experimentation with personal assistants and agents is only expanding as more people test and experience the potential power of agentic AI. Self-hosted deployments create false confidence while distributing security responsibility to users who often lack expertise to properly configure authentication, network binding, and credential protection.

Whilst in OpenClaw's case this is occurring in personal devices, this is also occurring through citizen development in businesses today. Experimentation with personal assistants and agents is only expanding as more people test and experience the potential power of agentic AI.

When Autonomy Becomes Personal

This brings questions of agency, governance, and responsibility into a new context. When autonomy is personal rather than institutional, many of the assumptions baked into enterprise security models begin to strain. The issue is no longer only how organisations govern agents at scale, but how autonomy itself is introduced, understood, and bounded when the operator is a single individual rather than a company.

Seen through this lens, OpenClaw is less a cautionary tale or paradigm shift and more a signal. It shows how quickly agentic capability is moving into everyday use, and how little shared understanding we currently have about governing systems that can act, persist, and adapt on a person’s behalf.

How We Look at This at Geordie

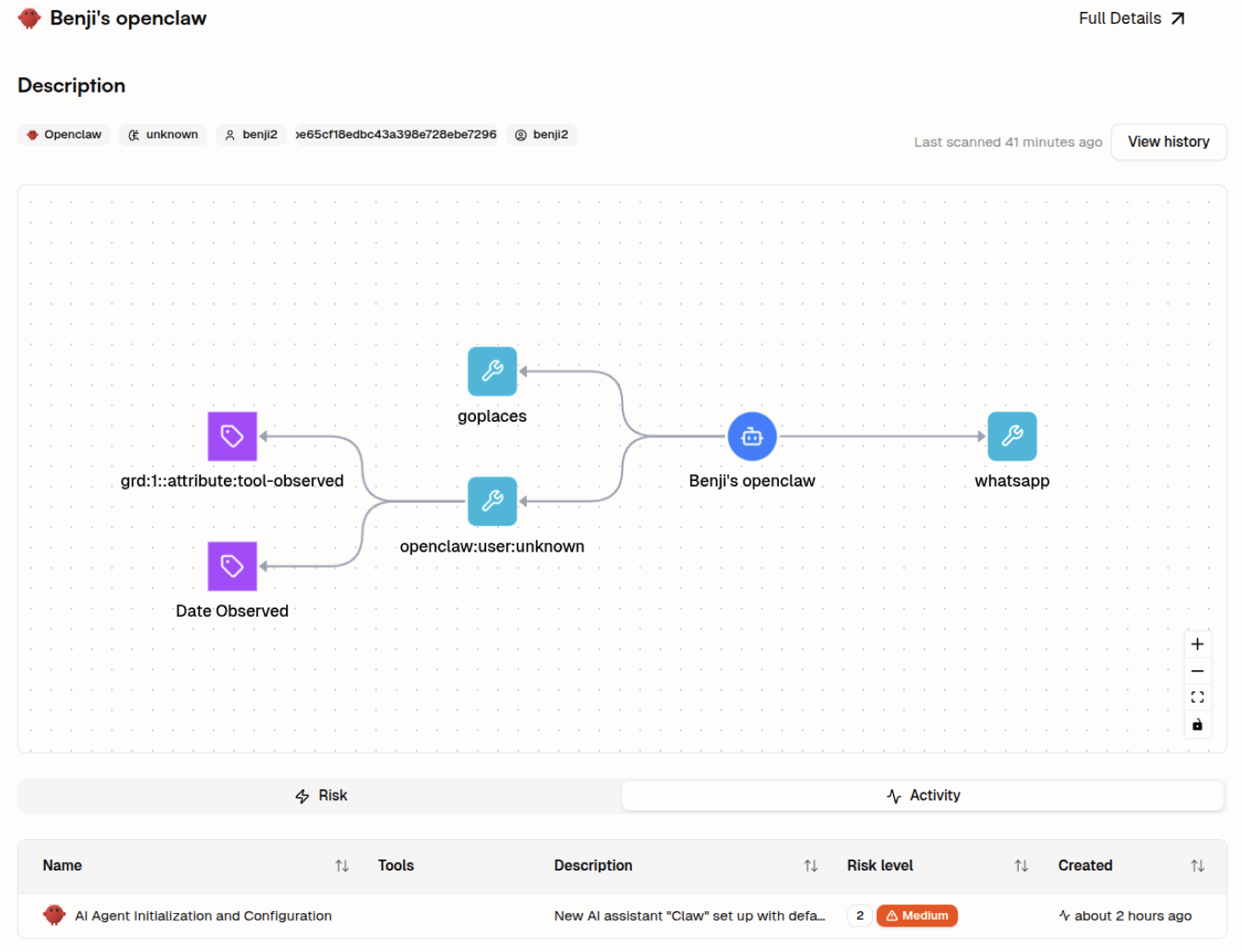

At Geordie, OpenClaw does not require a new category of risk modelling. We treat it the same way we treat other agentic systems: by analysing tool access, identity assumptions, memory use, and behavioural drift over time.

Our platform can identify OpenClaw deployments, map the tools and permissions they rely on, and observe how autonomy unfolds across tasks. The key signal is not exposure alone, but how decision paths and context reuse evolve once an agent is live.

The same approach applies whether autonomy sits inside an enterprise workflow or on an individual machine. What changes is the ownership model, not the underlying risk dynamics.

OpenClaw is not a paradigm shift, and it is not the most advanced agent ever built. Its significance lies elsewhere. It makes visible a transition that has already begun: autonomy is moving out of tightly managed enterprise platforms and into the hands of individuals. That shift does not introduce new technical primitives, but it does change the scale, ownership, and accountability of autonomous systems. Geordie was able to quickly adapt to OpenClaw coverage and it demonstrates the same threat modelling risks as other developing agents - the difference is that it's autonomy on an individual scale which makes governance gaps more impactful.

More Articles

.svg)